I have been reading a mixture of books recently and many of them are too good not to share, so I’d like to dip into each one and give you a glimpse of what makes the books stand out in a crowded bookshelf. I haven’t finished all of them so these are just outlines and glimpses.

A Hundred and One Days by Åsne Seierstad

Author Åsne Seierstad is a freelance journalist and who writes about everyday life in war zones. From her first hand experiences, she has written about Kabul, Baghdad and Grozny. I particularly enjoyed The Bookseller of Kabul, so I have finally picked up this gem, A Hundred and One Days, set in Baghdad during the US invasion of Iraq. I enjoy non-fiction and stories set in conflict areas so her books appeal to me. Seierstad focuses on the lives of Iraqi citizens, providing an insight into their days lived under the constant threat of attack, first from the Iraqi government and later from American bombs. She also describes in vivid detail the frustration felt by journalists in their attempts to sort truth from propadanda. The book looks at the ‘before,’ ‘during,’ and ‘after,’ of the war without casting moral judgement on the situation, and looks at everyday lives with a sharp understanding of human nature, a trait in her writing which I have enjoyed in her other books.

Orkney by Amy Sackville

Amy Sackville is a creative writing teacher at Kent University, and this is her second novel, set on a remote island in Orkney. It is a poetic and lyrical story of an unusual couple: a 61 year old literature professor and his pupil who is never actually named. The book spans their fortnight honeymoon in this barren landscape and, as she spends an obsessive amount of time by the sea, he realises how little he knows her. We don’t know why his wife is so obsessed by the sea, but it has something to do with her father, who disappeared when she was young. The language of the book is beautiful and intriguing, and I couldn’t put it down.

Amity and Sorrow by Peggy Riley

Riley is a writer and a playwright. There is so much to say about her but I’ll save it for my upcoming author interview next week. Released on March 28, this book is shocking and gripping story of a mother who rescues her daughters from a cult, their father and a fire, driving for days without sleep until they crash their car in rural Oklahoma. The girls, Amity and Sorrow, can’t imagine what the world holds outside their father’s polygamous compound. Rescue comes in the unlikely form of Bradley, a farmer grieving the loss of his wife. This is an unforgettable story which I was fortunate enough to receive as an advanced reader copy. I would recommend picking it up when it is released in the next few weeks. It has already had some wonderful reviews.

First Light by Charles Baxter

I discovered this out of print gem and managed to find a second hand copy. Charles Baxter’s short stories have appeared in the Best American Short Stories and in two of his own collections. This novel, his first, was supported by a Guggenheim Foundation grant. He takes us backwards through the lives of Hugh and Dorsey Welch who are brother and sister. We meet them as adults, while Hugh is a Buick salesman and Dorsey is an astrophysicist, and discover their dark and difficult pasts. The author traces their paths back to the day of Dorsey’s birth with an unusual subtlety. His opening paragraph includes this vivid description: ‘Hugh keeps both hands near the top of the steering wheel the way cautious men often do, and he does not turn to argue with her, not at first.’

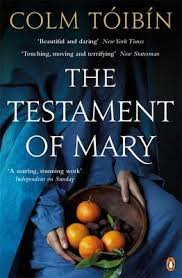

The Grant Book of the Irish Short Story

I am reading both the Irish Short Story collection and the Best American Short Stories, but I wanted to focus on this collection in particular, edited by Anne Enright. Ireland has produced some of the world’s most celebrated short story writers and this, a collection of the best works of contemporary Irish short fiction writers, includes works by Roddy Doyle, William Trevor, Colm Toibin and Kevin Barry. It begins and ends with a road accident. The first, which proves fortuitous, involves an out-of-work labourer and a carload of nuns; the second – which is fatal – occurs when a mechanic decides to earn a few extra euros ferrying tourists to a shrine where a statue of Mary is said to weep. Between these two tales we meet a mother who finds her son suspected of abuse and we glimpse the consequences of Irish abortion law. The subjects are heavy and, sometimes dark, but the writing is tight and distinctive. My favourite story so far is John Banville’s Summer Voices. His book, The Sea, won the Man Booker Prize in 2005 and his short story is carried off with the same elegance of style with phrases such as these: ‘The radiance of the summer afternoon wove shadows about him.’ The story follows a young boy and girl who discover a body in amongst an almost eerie description of the landscape.

You must be logged in to post a comment.