One of the questions I’m most frequently asked as a writer is, ‘do you focus on plot or character?’ I predominantly write thrillers, so character is particularly important and often drives the story line (the plot). Jana in Take Me to the Castle and Leisl in Dead Drop are strong female protagonists. Their thoughts, lives and actions drive the plot.

It works well for short stories, particularly given the brevity of the craft and the constraints of needing to hook a reader quickly, drawing them into a story. When the reader is engaged with the character, they are more likely to engage with the story and understand the motives driving the character’s decisions and actions.

When a reader knows what a character has experienced and understands their weaknesses and specific character traits, the story makes more sense and the reader wants to go on the journey with them.

Who your characters are is much more intriguing than what they do in a character driven story. We don’t engage with perfection as readers, we engage with vulnerability. Vulnerability leads to trust and connection.

It works with fictional characters in the same way as in real life. The writer’s job is to make the reader care, and the most effective way to do this is to highlight a character’s fears, vulnerabilities, and internal conflicts. I’ve written more about this in other posts on plot writing here and here, as well as on the narrative arc.

Examples of character driven stories…

Of Mice and Men

Crime and Punishment

Brooklyn

A Man Called Ove

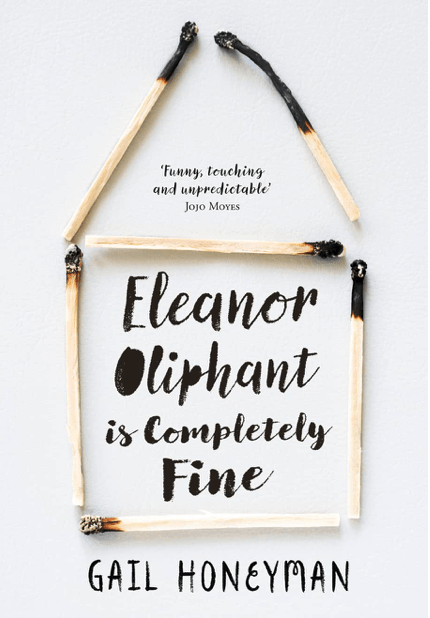

Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine

You must be logged in to post a comment.